•Reading and Writing on the Margins

•In Community, for the Community

•Spaces for Creation and Dissemination

•A Perspective from Production and the Market

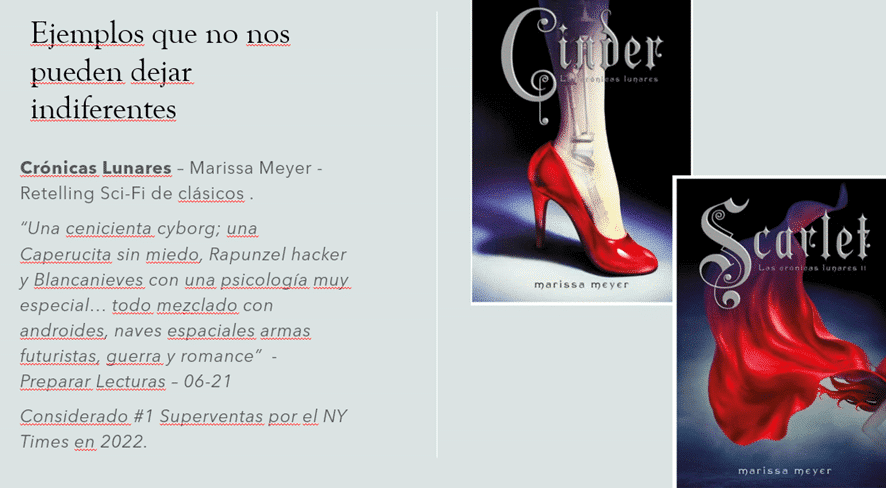

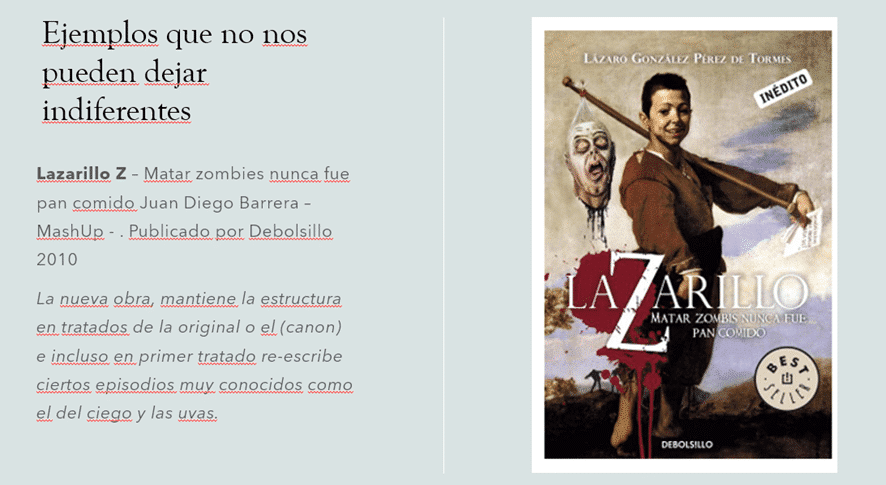

•Examples That Cannot Leave Us Indifferent

•Conclusions and Questions

First, I would like to mention that despite my background in literature, my career has mainly developed in the publishing industry. Therefore, you will notice a certain bias in this presentation towards that field, which, in turn, I believe has played a role in the “emergence” or at least the “categorization” of what we now call young adult literature. This presentation revolves around that segment.

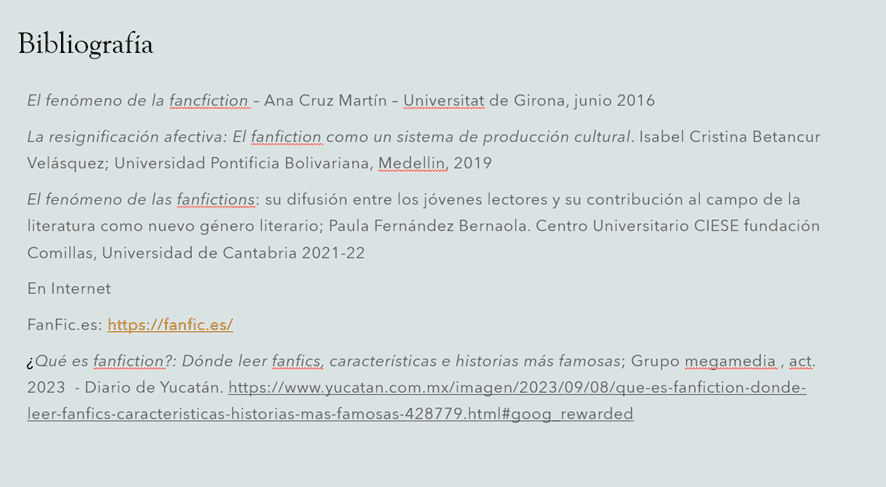

The Builders of Stories, Narratives, and Worlds

Historian Yuval Noah Harari’s main hypothesis is that it was the ability to imagine stories and believe in them that allowed Homo sapiens to organize into large groups. It was shared fictions that enabled unknown individuals to cooperate, build social systems, and adapt to different contexts.

Of course, we have imagined and told stories since long before margins existed. But the very act of establishing an official narrative, of selecting a group of stories as canonical, defines a way of doing things. In this case, it defines what literature is, what young adult literature is, who writes it, what is written, how it is written, and how it is shared and disseminated.

Today, we are living in a time of change—yet another. New means of production and dissemination, technology, and its new ways of reading and writing invite us to reflect on certain concepts within what we call literature and to look at what is happening outside the canon.

On the Margins.

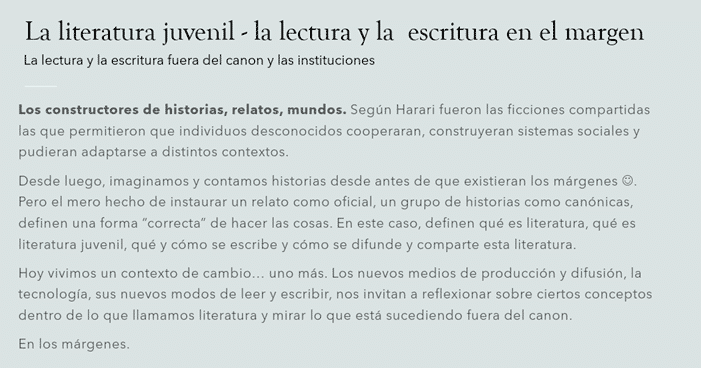

A large proportion of young people’s reading today takes place in new creative spaces associated with the internet, networks, and fan groups or communities of belonging (a highly adolescent characteristic, after all). This reading is characterized by being affective, reparative, liberating—seeking elements that are personally meaningful to the reader, connecting them to their own experiences, and consciously transforming them into writing projects. It is a participatory, active reading—not only through commentary but also through collective creative acts, debate, discussion, and new proposals. It is the kind of reading that would have delighted Cortázar—casual, carefree, rooted in fandom, capable of proposing and driving change. And, of course, such dynamics are not new to the literary world.

The concept of authorship is becoming blurred in both directions. On the one hand, writers of fanfiction or Wattpad stories openly acknowledge in their disclaimers that the work, characters, and worlds they are using do not belong to them. However, through their act of appropriation, they “steal” the original authors’ right to dictate the course of the story. They rewrite destinies and reshape characters as they see fit, molding them to their own needs and circumstances. On the other hand, this new rewriting, this new hybrid world born from fanfiction, does not tend to elevate the figure of the author as a singular voice. Instead, it belongs to the community—the writing is subject to the gaze of its peers, who critique and modify it. This collective perspective can even redirect narratives, alter endings, and change characters’ fates. And, once again, this is nothing new.

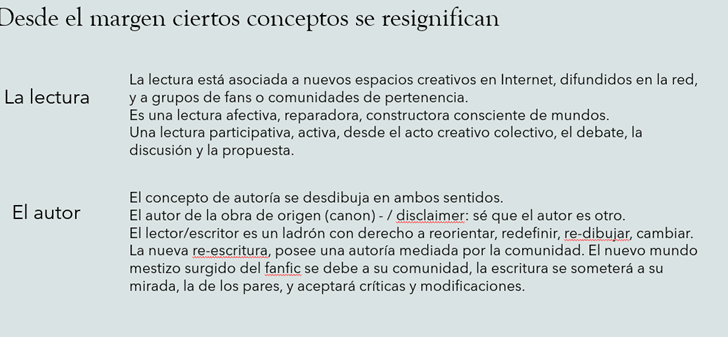

The Community: A Social and Cultural Perspective—Writing to Share, to Belong

The act of reading (oneself) and writing (oneself) as a way to shape a young social space.

“Fandom” refers to the community of passionate followers and admirers of a piece of entertainment, such as movies, TV series, books, comics, video games, and more. These fans express their enthusiasm through online discussions, content creation, fan art, conventions, and a variety of activities related to the work in question. The term itself is a hybrid, derived from the English words fan and kingdom. Fandom is our kingdom—the kingdom of fans. It is a space to share, to belong. A place where I can express myself in my own language and share my thoughts and wild ideas, knowing they will be read and reinterpreted by my community.

Motivation:

Completely adolescent in nature, their main driving forces are:

The famous What if…? – The endless creative game of rewriting: What would have happened if…?

Belonging – The need to be part of a community

Community – The social and emotional support networks that emerge

Sharing – The need to express oneself through writing as a form of liberation:

“Finding a space where I can truly be myself.”

Creating bonds – Strengthening connections through shared narratives

Fixing what I don’t like, what hurt me – Restoring a personal and desired sense of order

Writing:

This is marginal writing, created to be shared among peers. It is subversive writing because it challenges literary conventions, alters the “untouchable” classics, and modifies what has already been written and published by established authors. It is a form of writing that appropriates—stealing in order to reconstruct, reinterpret, and heal the universe according to one’s own needs.

This is a writing shaped by technology and community—fluid, interactive, and ever-evolving.

Language: A Living, Hybrid, and Participatory Expression

Like all marginal writing (let’s not forget the example of glosses or the illuminated marginal annotations in medieval books), this form of expression uses everyday, vernacular, and colloquial language—often “incorrect” by conventional standards. It is rarely edited, or only reviewed by peers. It is filled with neologisms, slang, and side notes.

This writing is multilingual and multimodal, hybrid, and uniquely ours. It integrates ideo-phonematic writing as a creative and emotional register.

Quality: “There’s so much garbage on Wattpad.” Yes. In proportion to the immense volume of works available. However, many high-quality, beautiful, and compelling works have emerged from it. Quality has always been a subjective and debatable concept. Yet even within these spaces, the community ultimately establishes its own valid standards—both for the fandom and the publishing market.

An Anecdote About My Daughter

My daughter, Marina, is a passionate reader, YouTuber, and literary advocate. She once tried to convince the local community library in her town to create a proper section for teenagers, as the existing one—according to her exact words—was so bad it made you want to cry.

After several meetings with the community members in charge, one of their conclusions was that teenagers don’t actually read. “They’re on their screens all the time,” said the elderly women from the neighborhood.

Marina tried to explain that much of that screen time was likely spent reading—comics, literature on online platforms, and so on. But they remained unconvinced.

As she left the library, she saw a 14-year-old girl reading on the street. She approached her and asked if she would be interested in a dedicated youth reading space in the library. Fifteen minutes later, Marina was surrounded by six teens passionately explaining why it was “super important” to have such a space in their community. Their arguments ranged from having a shared place for discussion to the need for a collaborative reading space.

Yes, many teens read on the internet. And they write, too. And this cultural and literary practice should not be ignored—it should be encouraged.

A significant portion of what young people read and write on various platforms falls under the category of fanfiction (or fanfics)—stories written by fans based on works that define their community, their fandom. A fandom is a group of passionate followers of a book, a person, a series… Fanfiction is, in itself, a tool for constructing cultural and social identity.

Homer (8th century BCE), Virgil (1st century BCE—commissioned by Augustus); all the tragedies and works written about various characters from the Iliad and the Odyssey, such as Lavinia by Ursula K. Le Guin (2008) / There are thousands of examples of what we call hypertextual constructions throughout the centuries. The rewriting of classic tales and myths is also part of this long list. The influence of the community, the readers, and their actions on the work also has historical examples: We could mention, for instance, how the apocryphal second part of Don Quixote, which circulated around 1611 (Avellaneda), was very likely, along with the success of the original first part, the reason for the appearance of the second part written by Cervantes in 1615. And it is certainly responsible for Cervantes’ dialogue between both versions within the work itself. From there, we reach reflections on the power of reading, rewriting, and the literary value that Borges proposed with Pierre Menard in 1939.

But in the 19th century, perhaps the idea of the fan community emerged with greater force. A well-known example was the case of Sherlock Holmes fans. A highly active community that, outraged by Sherlock’s death, forced Conan Doyle to bring his character back to life after he had killed him in a previous work.

Likewise, the serialized publication of novels in the 19th and 20th centuries—from Verne to Salgari—and the way this publication format and the reactions of readers and fans influenced the final works, are part of the historical corpus preceding fanfics and participatory writing.

Perhaps the clearest precedent of fanfiction comes from fanzines, magazines created in the late 19th century by groups of fans of certain works. These were published in an artisanal manner and were also shared within closed groups of fans. In other words, they were already publications made by fans for fans. The most famous ones: Spokanalia and T-Negative (both in the USA), associated with the phenomenon generated by the Star Trek series and its fans, the Trekkies. Some fanzines still exist today.

Fanfiction is its natural heir. It is a work born from another work, an expression of the emotional bond a fan maintains with a piece of media, and it is also a vehicle for communication and participation within a community. The work is both unique and transformative. And it waits to be accepted, legitimized within its environment.

Fanfiction at this point has widespread dissemination and features its own themes and genres, from Fantasy to Sci-Fi. It also has classifications by age group and its own jargon related to content: crossover refers to the mixing of one or more series, Alternative Universe / Fix-it / Shippers are part of this terminology.

There are currently many creative spaces where young people read and write not only fanfiction but also original works. Here, I will mention what I believe to be the three most important ones:

Fanfiction.net, created in 1998, emerged as an automated archive site for fanfiction. It is the most famous in the English-speaking community, designed by Xing Li, a programmer from Los Angeles. On this platform, we find all types of fanfiction, distributed by categories and under the motto “Unleash your imagination.”

Archive of Our Own (AO3) is a nonprofit organization created by fans in 2007 with the goal of providing access to and preserving the history of fan-created works and “fan culture.” It is considered the website that gathers the highest-quality or most reputable and well-written fanfiction. It has no censorship, unlike Fanfiction.net, which, for example, prohibits works based on real people or those with explicit sexual content. Archive of Our Own belongs to a larger structure called the Organization for Transformative Works.

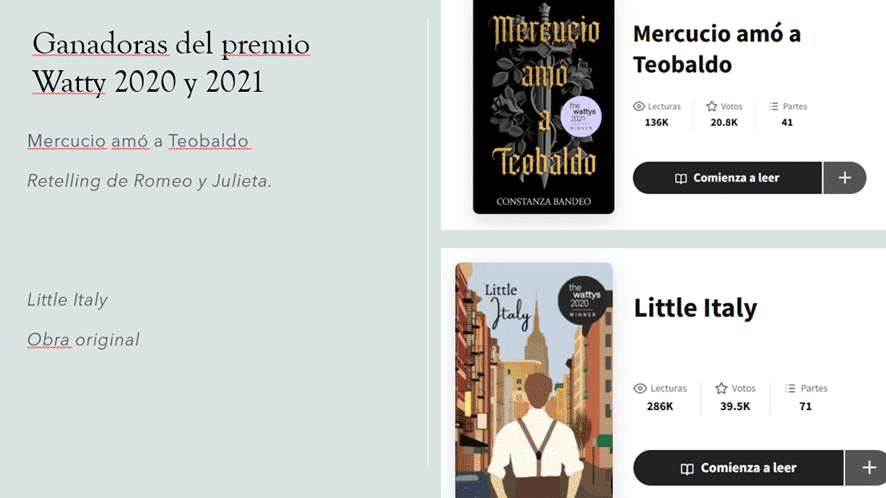

Wattpad, created in 2007 by two Canadians who wanted reading to be “accessible from all devices for all people.” Their goal was to become the largest digital literature distributor in the world—and they have achieved it.

By 2011, it already had 1 million users. One of the first works to transition from the internet to become part of the young adult literature canon was The Kissing Booth, published by Penguin Random House, which in 2018 was adapted into a film on Netflix (The Kissing Booth). It was written on Wattpad by a 17-year-old author, Beth Reekles.

According to its own website, Wattpad is a space where 97 million people spend part of their lives immersed in original stories. Wattpad has democratized storytelling for a new generation of writers from diverse backgrounds within Generation Z.

Wattpad is multi-device compatible, and it is, as a whole, a social network for reading and writing enthusiasts. Additionally, on this platform, readers can leave comments on each chapter and even on each line, offering a unique and interactive reading and writing experience.

A new model of production has been in development for decades, from self-publishing and self-editing to publication on Amazon, audiobooks…

Alternative or traditional financing processes. Crowdfunding through collaborative platforms, reader awards on platforms; traditional publication by major publishing houses that search for their future authors among those with the most readers on reading and writing platforms.

Dynamic distribution models: fandom, specialized fan conventions, YouTubers.

Finally, following the trajectory of major canonical works, script adaptations for movies or series also distributed on streaming platforms.

What is young adult literature? I think it’s important to reassess the term and consider that it would be extremely interesting to define it as literature written by young people for young people. Until now, it has almost been treated as a demographic category rather than a literary one—perhaps we should rethink this.

A reflection on reading and writing models. Under the light of new technologies and the phenomena inherent to pop culture. What we call affective reading and participatory reading, appropriation, and rewriting have shaped our humanity since the dawn of time. This ancestral and inexhaustible drive to invent and reinvent stories and share them is an inherent practice of our very humanity; in fact, according to anthropologists, it is one of our defining traits: we are storytellers. Is our way of reading the same now as it was 50 or 100 years ago? And our way of writing? How do technology and phenomena like artificial intelligence positively and negatively impact our creative capacity and, above all, our literary capacity?

Paradoxically, these new forms bring us back—through technology—to certain communal, participatory traits that shape a cultural literary space that is active, young, and strong. It is important not to underestimate it.

I believe this point, which I have already mentioned and which is also present in current discussions, should not be disregarded. I think we are facing a generation of young people who read a great deal, perhaps even more than previous generations. We could debate how and what they read, but one thing is certain: they read. And, above all, it is a generation that writes far more than previous generations. In their own carefree way, with this somewhat chaotic texture that has become a distinctive trait of pop culture, it is a generation that writes—and sometimes, they do it very well ????.